For quite some time, I had been planning to write about my understanding of the attention mechanism. It took a while, but I have finally finished. Attention is one of the most important innovations in modern AI. In fact, it is the backbone of the current AI boom.

I originally planned to write about the Transformer architecture directly, but since attention is the core innovation that powers Transformers, I decided to start with attention first.

The Transformer was first developed for natural language processing. Before we explore attention, it helps to briefly look back at how text was traditionally processed and what problems researchers faced. This background makes it clear why attention and later the Transformer became necessary.

Before attention and Transformers, most NLP models were built on recurrent neural networks.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) were designed to process sequential data such as text, speech, or time series data. Rather than looking at all the input at the same time, an RNN processes it step by step. As it goes, it keeps a kind of memory called a hidden state and passes it along.

In NLP, when an RNN reads a sentence, it goes word by word. With each new word, it updates its hidden state. It does this by combining two things:

This hidden state is like a running summary of what the RNN has read so far. For instance, if the model sees the sentence:

“Goku throws the Spirit Bomb at Frieza because he is desperate”

![]()

The hidden state after each word tries to represent the meaning of the sentence up to that point. For example, after reading "Goku" the state encodes that Goku is the subject. After reading "throws" it adds the action. After reading "Spirit Bomb" it adds the object, and so on.

Because it builds understanding word by word, RNNs can capture the order and timing of information. That makes them very useful for working with language.

RNNs suffer from two main problems.

Training instability for long sequences

When training RNNs, gradients must flow backward through many time steps. As sequences grow longer, gradients can become very small or very large, making learning difficult.

Compression of all information into one state

The entire history of the sequence must be stored in a single fixed-size hidden state. As new inputs arrive, older information can be weakened or lost.

To see this, imagine the RNN processing "Goku throws the Spirit Bomb at Frieza because he is desperate". By the time it reaches "desperate", the representation of "Goku" has been transformed ten times. The vector that once clearly pointed to "Goku" in semantic space now points to a mixture of all ten words, with "desperate" dominating the direction. Fine details from earlier words can easily disappear as more data is processed.

LSTMs and GRUs are improved versions of RNNs that are easier to train. They use parts called gates to manage how information is stored and changed.

Unlike simple RNNs, which rewrite their memory at every step, LSTMs and GRUs can learn to do three things:

For example, in the sentence “Goku throws the Spirit Bomb at Frieza because he is desperate,” an LSTM can learn to keep the subject “Goku” in its memory, while ignoring less important words like “the” or “at.” Later, when it reads “he,” the saved memory of “Goku” helps it understand who “he” refers to.

The gates work like filters, letting important details pass through without being erased. This fixes the problem earlier RNNs had, where information would get overwritten too quickly.

Overall, LSTMs and GRUs are more stable to train and can understand longer-range connections in text better than basic RNNs.

Even with these improvements, LSTMs and GRUs still work on the same basic principle.

At each step, they must squeeze all past information into one single, fixed-length vector. This causes a few key problems.

Fixed memory size

No matter how long or detailed the input is, it has to fit into the same sized vector. Think about a paragraph describing several characters, places, and events. Even the cleverest gates can't perfectly pack all that meaning into, say, 500 fixed vector. Some detail will always be lost.

Deciding too early

The model has to choose what to keep and what to forget before it knows what will be important later. For example, when the model reads “Goku throws,” it must decide how much memory to save for “Goku” before it knows that, twenty words later, it will need to remember exactly whether the subject was Goku, Vegeta, or Gohan.

Indirect access to the past

Even if key details are stored, the model can only reach them through the current summarized state. The original, clear idea of “Goku” is gone and has been replaced by a compressed version. This summary may have lost small but important details.

For longer texts like sentences, paragraphs, or anything with structure, this approach can still lose important information.

The main problem with recurrent models isn't just how they learn, but how they remember things.

The process forces information to:

When the input gets longer or more complex, this method becomes less effective. A better system would let the model hold onto more of the original information and decide what's important when it needs to.

This idea is what led to the creation of the attention mechanism.

Attention works differently. It changes how a model uses past information.

Instead of forcing everything into one summary vector, the model keeps the full set of word representations. Then, as it processes each new word, it looks back at all the previous words and chooses which ones to focus on.

Let's use the same example:

"Goku throws the Spirit Bomb at Frieza because he is desperate."

When the model gets to the word "he", it can now ask: Who does "he" refer to? Attention lets it check every word that came before. It can give a high relevance score to "Goku" and maybe "desperate", a lower score to "throws" or "Frieza", and almost no score to words like "the" or "at". It then blends these word representations together, weighted by how relevant they are, to form a clear understanding of "he".

This happens for every word.

When reading "desperate", the model might focus on "he" and "is".

When reading "throws", it might focus on "Goku" and "Spirit Bomb".

Unlike an RNN, where the memory of "Goku" could fade over many steps, attention provides a direct link. The original representation of "Goku" stays in memory, unchanged and ready to use at any moment. The model learns not just what to store, but when and where to look.

This move from compressing everything in advance to retrieving information when needed is the big change from recurrent models to attention-based ones. It's this idea that later allows models like Transformers to handle very long and complex text.

You might be wondering: how can a model actually focus on a single word? What does focusing on a word actually mean? To understand how attention focus certain words, we first need to know how words are stored mathematically. The whole attention idea depends on being able to represent words as points in a space, where closeness and direction carry real meaning.

In 2013, Mikolov et al. made a big leap forward in how we represent words. Their paper, "Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space," showed that we could train models to turn words into lists of numbers, called vectors. In these vectors, mathematical relationships actually reflect language relationships.

Here's a famous example that shows how it works.

The most famous example from this work is the relationship between king and queen. In a well-trained word vector space, the math looks like this:

vector("king") - vector("man") + vector("woman") is very close to vector("queen").

Imagine a high-dimensional space where every word is a point. To picture it, think of a 3D space where words float in groups. Similar words cluster together. For example, words like mango, orange, and strawberry would be near each other because they are all fruits. Words like car, truck, and bicycle would form another cluster because they are vehicles.

In this space, the word "king" is close to "man," and "queen" is close to "woman." Here's where it gets interesting. If you take the vector for "king," subtract the vector for "man," and add the vector for "woman," the result points almost exactly to "queen."

This works because the math captures an abstract relationship. The direction from "man" to "king" represents the idea of "royalty." Adding that same "royalty" direction to "woman" leads you to "queen." In this way, the space learns that the relationships between words can be expressed as simple geometric steps.

![]()

For better understanding, check out this video by 3B1B: Link

Word vectors create the foundation that attention uses. Each word becomes a list of numbers, like 300 numbers that represent its meaning. Attention works directly with these lists, measuring how similar they are to each other and blending them based on how relevant they are.

Without this kind of word representation, attention wouldn't have anything meaningful to compare or weigh. The big insight from Word2Vec was that we could turn separate words into points in a continuous space where "closeness" means "similar meaning," and the directions between points capture real relationships.

Take the word "apple" as an example. On its own, it could mean the fruit or the tech company. In the vector space, the word "apple" sits somewhere between these two meanings. But in a sentence like "I ate a red apple," the model can look at nearby words like "ate" and "red" to understand that here, "apple" is closer in meaning to "orange" or "banana" than to "Microsoft" or "Google." Because words are numbers, attention can calculate these relationships directly.

The same idea works for a word like "bank," which can mean a financial place or the side of a river. In the sentence "I deposited money at the bank," attention can focus on the words "deposited" and "money" to lean toward the financial meaning. In "I sat on the bank of the river," the words "river" and "sat" will guide attention toward the meaning related to land near water.

There are several types of attention, each with its own purpose.

Self-attention allows words in a sentence to look at other words in that same sentence. For example, in “Goku throws the Spirit Bomb at Frieza because he is desperate,” the word “he” can look directly at “Goku” to understand the reference.

Cross-attention connects two different sequences. It's especially useful for tasks like translation, where words in one language need to align with words in another.

Multi-head attention runs multiple attention mechanisms at the same time. Each one can learn to focus on different kinds of relationships, like who did the action or what the action was.

For our purposes, we'll focus on self-attention. It's the core of how transformers work. Once you understand how a word pays attention to other words in its own sentence, the other types are easier to grasp.

Let's return to an earlier example where the word Apple could refer either to the fruit or the technology company.

The main job of attention is to help the word apple pick the right meaning based on the words around it.

For example, in the sentence “Buy Apple phone”, the surrounding words Buy and Phone should push the meaning of Apple toward the technology company.

In the sentence “Buy green apple”, the words Buy and Green should pull it toward the fruit meaning.

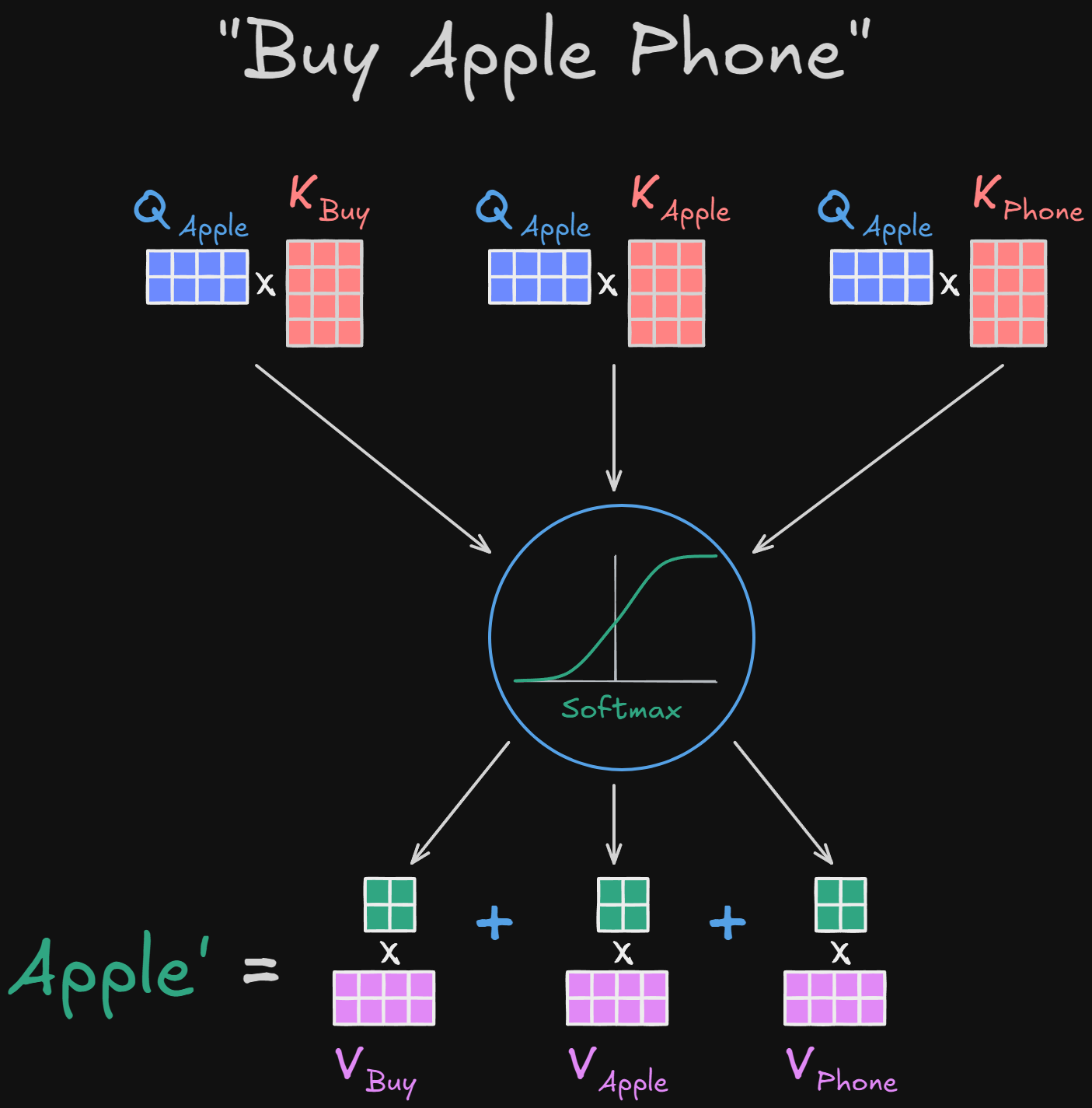

So for the first sentence, “Buy Apple phone”, the updated representation of the word Apple after attention might look something like this:

vector(Apple') = 0.1·vector(Buy) + 0.5·vector(Apple) + 0.4·vector(Phone)

Here, is the new representation of the word Apple, now aware of its context. The other words in the sentence shape this vector. Because Phone has a stronger influence than Buy, the resulting vector takes on more properties related to technology, pushing Apple toward that meaning.

Likewise, for the sentence “Buy green apple”, we might get a result like this:

vector(Apple') = 0.2·vector(Buy) + 0.3·vector(Green) + 0.5·vector(Apple)

In this case, Buy and Green influence Apple so that its updated vector leans toward the fruit side.

In the same way, every word in a sentence gets an updated representation based on its relationship with the other words. For our first sentence, it might look something like this:

The numbers above are just examples to show influence. Higher numbers mean a stronger influence. For instance, Phone influences Apple more than Buy does.

You might now ask: how do we actually calculate these influence numbers?

To simplify, let's imagine we represent meaning on a simple 2D plane. We'll place “Phone” at coordinates (0, 4) and “Fruit” at (4, 0). The word “Apple,” before context, might sit in the middle at (2, 2). To measure how similar two vectors are, we use a mathematical operation called the dot product.

We use dot product instead of cosine similarity because it works better for scaling in matrix operations later.

If we calculate the similarity between Apple and each word:

We can represent this as matrix multiplication as well:

Here,

Applying this to our example,

This gives us the similarity scores [4, 8, 8] for Buy, Apple, and Phone respectively.

Now we combine them with weights:

However, these similarity scores are still raw numbers with no upper or lower boundary. We need to convert them into normalized weights that reflect how much each word contributes. How can we turn some numbers into a probability distribution so that we know how much it contributes? YES! We use softmax:

So the final weighted representation is:

We repeat this process for all words in the sentence.

But there remain some issues:

So far, everything we've described uses fixed word vectors and fixed math. The dot product measures similarity, softmax turns those numbers into weights, and a weighted sum creates the new vector. But nowhere in these steps are there any settings that can be adjusted based on data.

This means the model can't learn or improve from examples. For instance, take these sentences:

A good model should learn that phone strongly suggests the technology meaning, and eat strongly suggests the fruit meaning. In our current setup, the influence of words like phone or eat depends only on their fixed starting vectors. If those vectors aren't perfectly placed from the beginning, the model has no way to fix that.

In other words, the model can't pick up on patterns like “when apple is near phone, focus on tech features” or “when apple is near eat, focus on food features.” All the relationships are frozen into the word vectors and the math. Training data can't change how attention works, because there's nothing to change.

That makes this version of attention static. It doesn't learn from mistakes, and it can't specialize for tasks like translation, classification, or answering questions.

Another problem is that we use the same word vector in every part of the calculation. The vector for apple is used both to ask, “Which words should I pay attention to?” and the vector for phone is used exactly as it is to answer that question.

This makes the dot product symmetric:

Mathematically, these two values are the same. But in meaning, these two interactions are not the same.

In the sentence “Buy apple phone”, we want apple to look at phone and ask, “Does this word help define my meaning?” We don't want phone to ask the same question about apple in the identical way. The roles of the words are different, but our current method treats them as interchangeable.

This also means the model can't capture one-sided relationships. For example, phone might be very important for defining apple, but buy might be much less important for defining phone. Using the same vector for everything makes these kinds of lopsided relationships impossible to represent.

Because we use the same vectors everywhere, all interactions end up symmetrical and the same. The model can't express something like, “This word matters a lot when understanding apple, but not as much when understanding phone.”

These two issues point to a deeper limitation. We need a way to add learnable parameters and to let the same word play different roles depending on the situation.

Alright, so how do we add learnable parameters? Yes! by introducing weights.

Instead of using the raw word vectors directly, we transform them using trainable weight matrices. These matrices are parameters the model learns during training, just like in any other neural network. This lets the model figure out which relationships are important for a specific task.

Think of a weight matrix as a filter or a lens. The original word vector holds many features, but the lens chooses which ones to bring into focus. By learning different lenses, the model can view the same word in multiple ways.

Let the vector for a word be:

We now add a learnable weight matrix, , and project the word vector into a new space:

The values inside are learned from data. During training, the model updates these numbers, just like it does in other layers. This is what makes attention trainable.

However, using just one weight matrix is still limiting. Even with learnable parameters, a single projection forces every word to play the same role during the attention process. The same transformed vector would be used to decide what to pay attention to, to compare words with each other, and to provide the actual information that gets blended into the output. These are different jobs, and mixing them into one representation restricts what the model can do.

Take the sentence "Buy apple phone." When understanding the word apple, the model needs to ask a question like, “Is there a word nearby that tells me if I'm a company or a fruit?” Meanwhile, the word phone needs to signal that it's relevant for answering that question, and it also needs to provide tech-related information that should shape the meaning of apple. Using separate weight matrices allows the same word to be projected differently for each of these roles, helping it to ask questions, serve as a comparison point, and supply meaningful updates separately.

This brings us to the idea of using three different projections of the same word.

For each word vector ( ), we introduce three separate learnable weight matrices:

Instead of using the same representation everywhere, we project the same word into three different spaces:

These are called the query, key, and value vectors. Although they all originate from the same word vector, they serve different purposes in the attention mechanism.

To understand why this separation is necessary, consider again the sentence:

"Buy apple phone"

Focus on the word apple. When the model processes apple, it is not simply trying to collect information from all other words. Instead, it first needs to decide what kind of information it is looking for. In this context, apple should be asking something like “is there a word here that tells me whether I am a company or a fruit?”. This intent is captured by the query vector ( ).

Now consider the word phone. When phone is compared against apple's query, it should present itself in a way that answers this question. The key vector ( ) is designed for exactly this purpose. It does not represent all properties of phone, only the aspects that are useful for being matched against queries.

Finally, once the model decides that phone is important for interpreting apple, it needs to extract the actual information that should influence apple's meaning. This information is carried by the value vector ( ). Unlike the key, the value is not used to decide relevance or compute attention scores. Instead, it encodes the actual semantic features that should be transferred once a word has been considered important, and these features are aggregated through the attention weights to form the final context-aware representation.

This separation is crucial. The features that help decide relevance are not necessarily the same features that should be passed forward as information. By learning three different projections, the model can specialize each representation for its role.

Because of this design, interactions between words are no longer symmetric. When apple attends to phone, we compute:

This measures how well phone answers the question produced by apple. In contrast, when phone attends to apple, the computation becomes:

These two quantities are generally different, because queries and keys are produced using different weight matrices. This allows the model to represent directional and role-specific relationships.

So, in a nutshell, the attention mechanism can be thought of as a question-and-answer process between words. Consider the sentence:

"Buy apple phone"

In this way:

This analogy shows why we need three separate projections: each word can simultaneously ask a question, respond to other words, and provide content, all in a task-specific way.

For a given word, we compute its similarity with all other words by taking the dot product between its query and the keys of all words in the sentence:

Each score reflects how relevant another word is to the current word, given what the current word is looking for. These scores are then normalized using softmax:

This converts raw similarity values into a distribution that indicates how much attention should be paid to each word.

Finally, the new representation of the word is computed as a weighted sum of the value vectors:

At this stage, only the value vectors contribute to the output. Keys and queries are used solely to decide where to attend, while values determine what information is actually combined.

Because ( ), ( ), and ( ) are learnable, the model can adapt its attention behavior through training. Over time, it can learn that provides strong evidence for interpreting as a company, while may be less informative. More generally, it learns task-specific notions of relevance and information flow, rather than relying on fixed geometric relationships in the original embedding space.

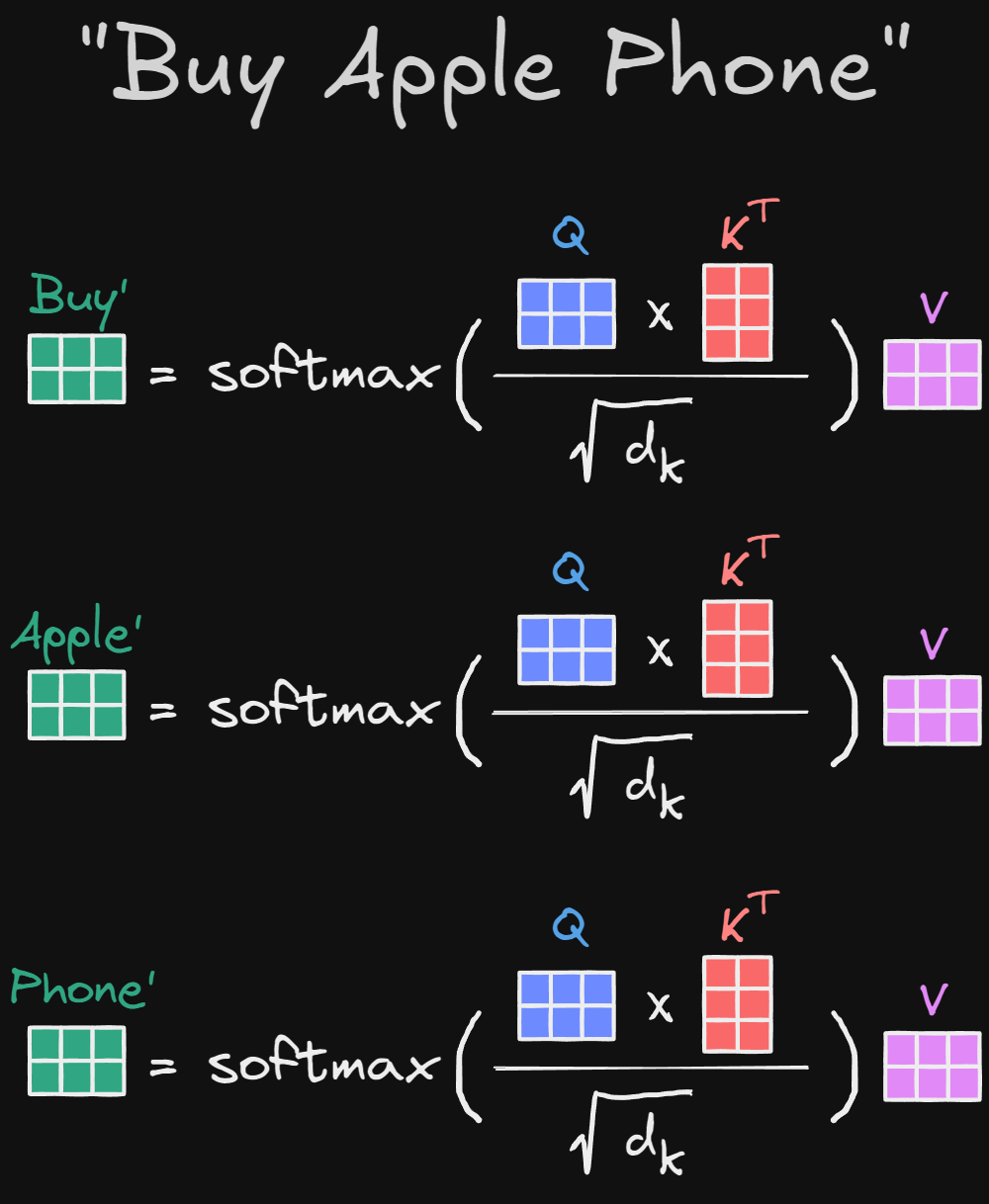

So, putting everything together, the attention operation can be written as a sequence of three steps:

This leads to the familiar formulation:

However, in the Attention Is All You Need paper, the authors introduce a small but important modification:

Here, is the dimensionality of the query and key vectors. This naturally raises the question: why do we divide by , and what problem does it solve?

In a single sentence: dividing by keeps the magnitude of the dot products under control so that the softmax does not become overly sharp.

But to understand why this matters, we need to look at what happens to dot products as the dimensionality increases.

The dot product between a query and a key is a sum over all dimensions:

Each term contributes a small amount to the final score. When the dimension is small, this sum contains only a few terms. As grows, more and more terms are added together, which increases the spread of the resulting values.

In probability theory, there is a rule that,

the variance of this sum grows linearly with the number of terms, meaning: The variance of is proportional to .

Here, Variance measures how far values are spread out from their mean. Larger variance means more extreme values, both positive and negative.

To make this clearer, let us look at multiple dot products, and compute their variance.

Consider several query–key pairs:

Now compute their dot products:

So the dot product values are:

First compute the mean:

Now compute the variance:

Now increase the dimensionality to . Consider the following query–key pairs:

Compute the dot products:

So the dot product values are:

First compute the mean:

Now compute the variance:

Compared to the case, the variance has clearly increased.

As we keep increasing the dimension, the dot product accumulates more contributions, and its variance grows accordingly.

This behavior becomes very clear when we simulate it. The following script repeatedly computes dot products between random query and key vectors of increasing dimensionality and measures their variance:

As the dimensionality doubles, the variance of the dot product also roughly doubles. This means the values in become increasingly spread out as grows.

When we apply softmax to those values:

So, when the variance of is large, softmax produces extremely peaked distributions. As a result:

This leads to unstable training and poor gradient flow, which we also know as the vanishing gradient problem.

To prevent this, we need a way to keep the variance of the dot products roughly constant as the dimension increases.

If we look carefully at the output, we can see that the variance grows proportionally to the dimension . So, the first idea might be to divide by .

However, if we divide by , we encounter the opposite extreme. Mathematically:

As the dimensionality increases, dividing by makes the variance shrink too much. For example, with , the variance drops to about , and the dot product values become extremely small. When we apply softmax to these tiny numbers:

This problem is called over-smoothing, here the gradients can flow through softmax, but they carry very little useful signal because every word gets almost the same attention. The model loses its ability to focus selectively on relevant tokens.

The fix is to keep the variance of the dot products roughly the same, no matter the dimension. This is why we divide by instead of .

This scaling keeps the variance of the dot products roughly equal to 1. For example, when , dividing by keeps the dot products in a range where softmax can clearly distinguish which words are more relevant, while still allowing gradients to flow smoothly.

Dividing by strikes the right balance: it prevents vanishing gradients and keeps the attention mechanism able to focus on the most relevant words.

You can see this effect in action using the following code snippet:

Alright, so when we put everything together, the complete calculation looks something like this.

At first glance, this looks like a lot of calculation. And you are right, there are many calculations to do. But here is the key point. Each calculation is independent from the others.

When calculating the new representation for the word "Apple", we do not need to know the result for the word "Buy" first. They can be worked out separately at the same time. This independence makes attention very different from older sequential models.

Why is this important? Because modern computer hardware, especially GPUs, is designed to do many independent calculations all at once. We can take every word in a sentence, figure out how they relate, and update all their meanings in one parallel operation. This is a major advantage. It lets us process full sentences or even entire documents much faster than if we had to go word by word in a fixed sequence, which is how older sequential models like RNNs work.

This is it! As for references, all the concepts, examples, and explanations reflect my cumulative understanding of the attention mechanism. You may find that some parts resemble or align with explanations from other articles, blogs, books, or lectures. It is not practical to list every source that contributed to this understanding, but I am deeply grateful to the many excellent resources, authors, and educators whose work helped build this understanding.